EVOLUTION OF JAPANESE FOOD

SERVING UP A COLORFUL, GASTRONOMIC HERITAGE

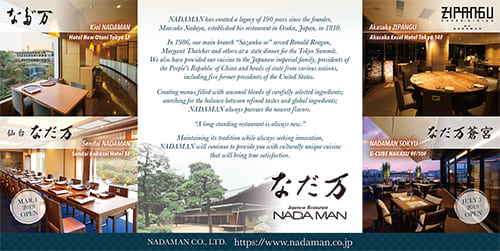

NADAMAN

Japan’s food scene makes waves almost every week, boasting colossal tuna, Michelin-starred restaurants and enough of an international ramen following to get even Gordon Ramsay curious.

Tens of thousands of international adventurers visit Japan each year just for the chance to sample what the country’s practiced chefs have to offer, and for good reason — it’s unbelievably delicious.

A taste of the past

Much of what makes Japanese food so enticing is its time-tested design. The term sushi, for example, has been used as a culinary descriptor since the Nara Period (710 to 794), and it has been through quite a transformative journey in the last millennium and a half.

Nare-zushi — the first instance of the word — emerged as an early method of preserving fish by laying cuts of freshwater trout or carp over vinegared rice and storing it overnight. Nare-zushi persisted during the ensuing feudal eras as a staple food before taking on its more recognizable appearance near the end of the Edo Period (1603 to 1868).

This peaceful era allowed for some culinary experimentation, prompting food carts throughout the Edo capital to start serving nigiri-zushi (literally “gripped” or hand-rolled sushi) in much the same style that can be ordered today. Soon, freshness and variety became a matter of high demand, giving birth to edomae-zushi that featured cuts of fish caught straight off the city’s shores. Fortunately for everyone, that delicious trend has stayed alive, and now “edomae” is a well-known moniker for high-quality fish among Tokyo’s eateries.

Food for the soul

NADAMAN

Sushi was certainly not the only edible achievement to blossom out of the country’s feudal years. In particular, the latter half of the Sengoku or Warring States Period (1482 to 1573) saw the introduction of kaiseki ryōri (traditional multicourse cuisine), one of Japan’s most decadent yet perhaps least understood culinary arts.

Part of what makes kaiseki ryōri difficult to understand is that there are in fact two distinct styles, each with its own origin and traits. Even more confusing is the disparity between the way they are written in Japanese — one meaning “banquet” and the other meaning “pocket stone.”

The origin of pocket stone kaiseki begins with the tea ceremony, specifically as it was cultivated under the noted Japanese tea master, Sen no Rikyu. Considered to be one of the most influential contributors to cha no yu, or the Japanese way of tea, Rikyu rejected overly austere formalities and instead placed emphasis on the beauty of simplicity and the once-in-a-lifetime experience of sharing tea with an amicable stranger.

Rikyu also did away with the alcohol-laden after-party that typically followed, offering in its place a simple pre-tea meal of a few carefully plated dishes. Though the meal itself would be humble in substance, Rikyu incorporated several elements of tea ceremony into its composition — cherishing the fleeting flavors of the season, paying mind to the ceramic dishware and overall presentation, and appreciating the atmosphere of serving communal food and drink.

Rikyu dubbed the meal “pocket stone” after a habit practiced by Zen monks in which they would place warm stones in the pockets of their robes near their stomachs to ward off hunger. It is thought that Rikyu used this metaphor to express that kaiseki was more of a food for the soul than an actual filling meal.

Model of modern Japanese fare

NADAMAN MAIN BRANCH SAZANKA-SO

In Rikyu’s time, however, kaiseki typically referred to a somewhat vivacious kind of cuisine (like the one he purposefully scratched from cha no yu) that was served to imperial court families and samurai households. This “banquet” kaiseki focused more on ornate presentation, colorful conversation and no small amount of sake. Despite their differences, both varieties of kaiseki ryōri survived to the modern era in an abstractly unified state, although some establishments are known to adhere to one style over the other.

While the origins of kaiseki ryōri are rather divergent, both have helped define some of the core tenets of modern Japanese cuisine. Raw ingredients are served in as fresh a state as possible to maximize their inherent characteristics. Seasonal ingredients are used expressively to convey respect for the impermanence of nature. Steamed foods, though often plated together, are prepared separately so as to preserve specific flavors that each deserve a moment of spotlight on the palate.

Most importantly, however, the histories of these foods demonstrate that appreciation of a meal does not start — or stop — with the food alone. Be it a multicourse banquet or a simple slice of fish over rice, there is a story behind every meal in Japan, and that is truly what makes them all the more appetizing.

URL: http://www.maff.go.jp/j/keikaku/syokubunka/culture/rekishi.html