TOHOKU TOURISM

Sponsored content

QUIET WONDERS OF THE UNTAMED NORTH

Everybody needs a break from the razzle and dazzle of the big city once in a while — and Tohoku is waiting with open arms.

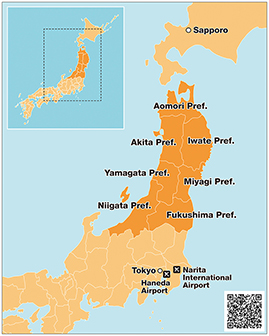

Comprised of the mainland’s seven northernmost prefectures — Aomori, Akita, Iwate, Yamagata, Miyagi, Niigata and Fukushima — the Tohoku region is characterized by its vast swathes of nature and the respectful passion with which its people celebrate their regional culture.

The nights in Tohoku are quieter and the trains less frequent, but this is by design. There is no urgent need to catch up to the likes of Tokyo or Osaka; rather, it is precisely this lack of similarity to such urban meccas that makes Tohoku a region of wonder.

Visitors can still find plenty of guided tours and travel packages to help add a little structure to their journey, but one of the bigger draws of vacationing in Tohoku is the opportunity to just be.

Take, for example, the Oirase Stream in Aomori Prefecture. With both a footpath and an automobile-accessible road, this nationally protected stream invites travelers to set their own pace as they gaze upon the babbling brooks, dancing waterfalls and abundant wildlife to be found throughout. With little more than a few wooden signposts to guide the way, there is very little to distract from the surrounding scenery — and that is just as the people of Tohoku prefer it.

Many of the region’s most charming attractions are directly related to how people commune with nature. The ambient hot spring towns, untouched gorges and snow-laden festivals all harken back to a time before handheld technology was so pervasive in everyday life, giving every visitor a chance to rediscover the harmony that humans have always shared with their environment.

The locally sourced ingredients in Tohoku further demonstrate the region’s humble reverence for what the earth can provide. Taro-based stews, soba noodles and grilled rice dumplings have long served as staple dishes in northern Japan. Simple and yet curiously sweet, these kinds of from-the-soil cuisine are also perfectly complemented by the many varieties of regional sake that have garnered critical acclaim here.

Yet good food, fine spirits and tranquil scenery would be naught without the people of Tohoku. Their unquestionable kindness and ardent respect for heritage is more than evident in the centuries-old festivals that still take place today — including Fukushima Prefecture’s Taimatsu Akashi Fire Festival and Nihonmatsu Lantern Festival, the origins of which date back to the 1600s. As many of these festivals have yet to reach nationwide popularity, repeat visitors and first-timers alike are all eagerly invited to participate.

Thankfully, reaching Tohoku is now more convenient than ever. The Yamagata Shinkansen, Akita Shinkansen and Tohoku Shinkansen offer frequent daily departures from Tokyo to the various prefectures (the Tohoku Shinkansen terminates in Aomori Prefecture).

Other transportation options include group-friendly charter buses provided by tourism associations and travel agencies, as well as direct flights from abroad to Sendai International Airport in Miyagi Prefecture.

The gateway to the great outdoors is wide open; come pay a visit and experience Japan’s wonderful heartland of Tohoku.

NATURAL BEAUTY

GREATER THAN THE ‘GRAM: EMBRACING FLEETING SIGHTS

When fall arrives, Instagram will surely be bombarded with the usual photographs of Japan’s crimson foliage. But no screen size or pixel count could possibly do justice to the breathtaking explosion of color that graces Tohoku.

While the seasonal hues of western Japan tease their own oohs and aahs from the crowd, the biggest difference in Tohoku is the sheer number of broad-leaved trees that make up its forests. Come fall, the large foliage paints the region anew to produce multilayered expanses of color that are rarely seen elsewhere in the country.

One such expanse is the Geibi-kei gorge in Iwate Prefecture. Formed by the Satetsu River, the gorge spans two kilometers and is bordered on both sides by 50-meter-tall limestone cliffs. Visitors can settle in for a 90-minute round-trip boat ride through the gorge that meanders around waterfalls, limestone caves and striking rock formations — all the while enveloped by every shade of yellow, orange and red imaginable.

Along the way, passengers can feed the plentiful river fish, try their hand at tossing undama (luck stones) into a wish-granting hole in the rock face, or simply take in the tranquil surroundings as they listen to the boatmen gently singing geibi oiwake, or local folk songs.

Down south in neighboring Miyagi Prefecture, travelers will find another jaw-dropping sight at Naruko-kyo gorge. This 100-meter-deep gorge is beautiful throughout the year, but the late October views from Naruko-kyo Rest House are nothing short of magical. Visitors should check the local Rikuu-Tosen Line train schedules and watch the train as it passes over the Ofukasawa Bridge that spans the forested gorge.

Afterwards, it’s well worth a visit to Naruko-onsen-kyo Hot Spring Village for a soak in the open-air baths. The village’s hot springs have been serving travelers for over a millennium; their popularity to this day serves as proof of the denizens’ ardent respect for the comforting warmth and cleansing benefits provided by these powerful natural phenomena.

Those in the mood to throw a little history lesson in with their fall excursion should pay a visit to Ouchi-juku, a historic post town in Fukushima Prefecture. Replete with thatched-roof houses, authentic meals and the impressive Takakura Shrine, this sightseeing location gives travelers an authentic peek at what it was like living in the Edo Period (1603 to 1868).

Visitors to Ouchi-juku are welcome to participate in a relaxing guided tea ceremony or sample some of the many soba dishes that the post town famously provided to travel weary daimyo on their annual pilgrimage to the Edo capital. Combined with the plethora of deciduous trees that span the surrounding hillside, guests can take in the unmistakable aura of rustic autumnal tranquility.

The true wonder of fall in Tohoku is that all five senses take part in the experience. Be it with the gentle sounds of river folk songs, the soothing touch of mineral-rich spring water, or the faintly sweet taste of expertly crafted soba — the charms of the region ensure that visitors not only see, but also feel the changing of the season. Such is the delight of northern Japan that has first-time tourists, practiced adventurers and even long-term residents leaving satisfied that they chose Tohoku for their fall travel destination.

A LAND SPECKLED WITH SNOW MONSTERS, COZY TRADITIONS

There are countless ways to highlight the charms of each season, but perhaps the best way to describe winter in Tohoku is with the phrase, “nothing quite like it.”

Though Japan offers plenty of skiing, hot springs and winter festivals, Tohoku in particular is home to some spectacular natural phenomena and cultural practices that are entirely unique — traits that have earned the region high praise from seasonal visitors both domestic and international.

Topping the list of sights unseen anywhere else would have to be the meteorological curiosities affectionately known as snow monsters. These can be found in three specific areas around Tohoku: Mount Hakkoda in Aomori Prefecture, the Zao region in Yamagata Prefecture and Mount Moriyoshi Ani Ski Resort in Akita Prefecture.

Known in Japanese as juhyō, the snow monsters are in fact pine trees that have accumulated large amounts of wind-borne snow spray. The sporadic storms and humidity levels in Tohoku constitute the perfect conditions to create these comically clumpy spectacles. The snow monsters can be spotted by cable car, from observation towers or even while skiing down the slopes, so visitors will have every opportunity to catch sight of them for themselves.

Yet while the wintry forces of nature are busy building snowmen, the men and women of the city of Yokote in Akita Prefecture have set to work making igloos for the Yokote Kamakura Festival. A folklore tradition exclusive to Tohoku, this festival dates back roughly 450 years and honors the deity of pure water.

By mid-February, the town will be dotted with about 100 freshly built igloos. Seated in them are local children who welcome passersby in to snack on amazake — a milky sweet, generally nonalcoholic form of sake — and chewy rice cakes. The inviting atmosphere and surprising warmth inside the lantern-lit igloos creates a jovial mood that draws together people of all ages and backgrounds.

Yokote Kamakura is one of the many koshōgatsu or “Little New Year” festivals in Tohoku typically held around the first full moon of the lunar calendar. Some of them — like the Namahage Festival in Akita Prefecture — are for warding off evil and praying for a bountiful summer harvest, but they all bring warm smiles to the chilly nights.

Of course, winter in Japan would not be complete without a soul-soothing dip in the hot springs. Tohoku boasts some of the most popular hot spring destinations in the country, including places like Osawa Onsen in Iwate Prefecture that have been selected as ideal for yukimi rotenburo — the picturesque experience of “getting snowed on while lounging in the open-air bath.”

Visitors should be sure to also stop by the charming Ginzan Onsen in Yamagata Prefecture. Featuring nostalgic wooden architecture and ambient gaslit street lamps, visitors to this picturesque hot spring village will feel their hearts melt well before they even set foot in the baths.

Low though the temperatures may be, spirits are high and smiles are wide during winter in Tohoku. The depth of tradition and community found in this region is proof of the solidarity that arises in the face of bitter climates. That — and the fact that the snow monsters now have their own official mascot — should be more than enough reason to pay Tohoku a jolly visit this winter.

RICH HISTORY & REFINED CULTURE

A LEGACY OF TEMPLE RICHES, SAMURAI ABODES AND NOH

Tohoku has a rich history and diverse cultural offerings, which include a gold-plated, 1,000-year-old temple, an elegant samurai neighborhood and a rural island with a vibrant theater tradition stemming from an exiled playwright. Few locations feature refined culture and exquisitely preserved history in such idyllic settings. Tohoku offers both at the same time.

Chuson-ji Temple in Hiraizumi, Iwate Prefecture, was founded in 850 and is a UNESCO World Heritage site. The wooded complex is nestled on a hillside above the fertile Kitakami River valley. While Chuson-ji features 400-year-old cryptomeria trees, eternal flames said to have been lit over 1,000 years ago and a museum with thousands of National Treasures and Important Cultural Properties, its crown jewel may be the marvelous Konjikido Golden Hall, which is the only structure on the property to survive in its original form. And what a form it is — the entire 12th-century building, minus the roof, is covered in gold leaf, much of it probably mined in Hiraizumi’s famous gold mines. The riches of the Golden Hall and the area’s mines may have led to the Legend of Zipangu, which was the belief propagated by Marco Polo that Japan possessed enormous wealth in gold. Konjikido now sits inside its own protective hall, alight in the dim space as if the gold itself were glowing. To visit Chuson-ji is to encounter centuries of Buddhist art and history in a peaceful rural setting.

While monks managed Japan’s spiritual matters, worldly affairs were left to the samurai. The refined culture of these warrior aristocrats can still be experienced in Kakunodate in Akita Prefecture, an area that boasts a remarkably well-preserved district of samurai residences. The town, which was at its height during the Edo Period from 1603 to 1868, is known as Little Kyoto, and while it is indeed smaller than the nation’s former capital, happily so are the crowds. Many of Kakunodate’s historical buildings are open to the public — as museums, restaurants, preserved family homes and inns — with others functioning as residences, in some cases for descendants of the original samurai families. If a stroll through the streets of Kakunodate is de rigueur, why not do it wearing an antique kimono from one of the town’s rental shops?

As splendid as Chuson-ji and Kakunodate are, monks need temples and samurai need mansions; this easily explains why they were built. Yet the presence of a refined form of theater on an isolated island in the Japan Sea is more difficult to figure out. As it happens, two political decisions are behind Sado Island’s flourishing noh scene. The first was the exiling of Zeami Motokiyo in the 15th century. Zeami was sent to the island for angering the shogun, but fortuitously for Sado he was also the person who perfected the art of noh. Centuries later, a noh actor’s son tasked with overseeing the island’s gold mines helped to further establish the art form here. Today, noh performances are given at numerous shrines and temples on the island. Once there was said to be as many as 200 noh stages on the island. Though the number has since decreased to around 30, this is still more per capita than anywhere else. Most of the performances take place outside, so they’re held during the warmer months, almost every weekend in summer.

PILGRIMAGES THROUGH THE GLORY OF ANCIENT FORESTS

As if glorious scenery, ancient cedar forests, elegant shrines and mountain-to-table dining were not enough, visiting the Three Mountains of Dewa is said to offer pilgrims the chance to overcome their present troubles, come to terms with the past and encounter their future selves.

All this is possible at the Dewa Sanzan — Mount Haguro, Mount Gassan and Mount Yudono in the heart of Yamagata Prefecture. The mountains began their rise to religious prominence nearly 1,500 years ago, when Prince Hachiko, the son of an assassinated emperor, arrived in the area to begin a life of spiritual devotion. His practice began on Mount Haguro and eventually expanded to include Mount Gassan and Mount Yudono, with the deities for the three mountains now enshrined on the Haguro summit. The mountains are located in what used to be Dewa province, hence the name.

To this day white-clad pilgrims, known as yamabushi or mountain ascetics, walk the three mountains seeking renewal of body and mind. One of the highest spiritual attainments is considered to transforming into a sokushinbutsu, which is a kind of mummified “living Buddha.” Two nearby temples have sokushinbutsu — Dainichibo and Churen-ji. There are said to be only 16 living Buddhas in Japan. The presence of eight in Yamagata Prefecture indicates how seriously the area takes religious practice. Not to worry, the paths can be enjoyed by anyone with a love of nature, architecture or history.

Mount Haguro can be considered the main shrine and it is also the most accessible, being walkable year-round. It is home to some of the more famous sites on Dewa Sanzan, one being a five-story pagoda believed to have been first built in the 930s. The current structure dates to 1372. Near the pagoda a section of a path is lined by 580 cedar trees, all of them centuries old. This impressive corridor was given three stars in the Michelin Green Guide Japan.

Mount Gassan is the highest of the Dewa Sanzan and is inaccessible in winter due to snow. During hiking season, it offers impressive views from its treeless peak. It is possible to climb up Mount Gassan then over to Mount Yudono in a day. Typically pilgrims do not summit Mount Yudono, but visit the shrine on its northern flank. Local businesses can facilitate yamabushi pilgrim experiences that include lodging, meals and religious instruction. For those who wish to create their own experience, pilgrim inns can be found around Mount Haguro.

Not to be missed on a visit to the Dewa Sanzan is a meal of shōjin ryōri, a term that is often translated simply as “vegetarian food” but in fact carries spiritual connotations of purification and renunciation. Shojin ryori is sometimes described as an “experience” because it entails so much more than just eating. Usually served in sparsely decorated tatami rooms on low lacquered tables, a single meal can include dozens of tiny dishes, each prepared separately using seasonal ingredients. To expand the gastronomical experience beyond the table, it is possible to join foraging tours that venture into the forest to gather mushrooms, vegetables and spices.

Northern Tohoku has more to offer in the realm of ancient spiritual traditions. Farther north is Bodai-ji Temple on Mount Osore in Aomori Prefecture. Mount Osore is one of Japan’s three holy mountains and literally means “fear mountain” because of its purported resemblance to Buddhist hell. To the east in Iwate Prefecture is the town of Tono that is known as a rich repository of folk beliefs and oral traditions.

ARTISANAL CREATIONS

CARVING NEW LIFE INTO WOODWORKING CUSTOMS

The Tohoku region has abundant forest resources that local people have incorporated into their culture and traditions since ancient times. Various traditional crafts and housewares made of wood have been made and used until today, as well as others that have been reevaluated in recent years by younger generations and people from outside Japan.

Akita Prefecture’s prominent craft are magewappa made from Akita cedar trees. The term “mage” means “to bend” and “wappa” refers to a cylindrical container made of wood.

Dating back about 1,000 years and believed to have been first created by woodcutters, magewappa items have traditionally been used as food containers. The craft then became popular about four centuries ago in the area currently known as Odate in Akita Prefecture at the eastern end of the Shirakami mountain range that forms part of the Shirakami-Sanchi UNESCO World Heritage site. The site includes the last of the virgin forests of Siebold’s beech that once covered much larger areas in northern Japan.

It was the daimyo or Japanese feudal barons of the region that promoted the use of Akita cedar timber, and local samurai engaged in the production of magewappa as a side business. Farmers were encouraged to carry timber from forests as a replacement for rice tax.

Although magewappa containers once suffered a lack of demand due to the extensive use of plastic products, they have recently been gaining local recognition as an environmentally sustainable product. At the same time, with the growing interest toward Japan’s bento culture from abroad, magewappa are also attracting international attention, sparking fresh demand.

At Shibata Yoshinobu Shoten in Odate, visitors — with reservations — can experience a two-hour magewappa workshop and make either a bento box or a breadboard.

http://magewappa.com/ (Japanese only)

MIYAGI PREFECTURE SIGHTSEEING SECTION

MIYAGI PREFECTURE SIGHTSEEING SECTION

Kokeshi are wooden dolls that have been crafted since the end of the Edo Period (1603 to 1868). It is said that the dolls were originally crafted and sold in the hot spring areas in the Tohoku region as souvenirs for children.

Although kokeshi are simple dolls that consist only of a head and a torso, their facial expressions are what makes them distinctive and appealing. Kokeshi faces, as well as the flowery or geometric patterns on the dolls’ torsos, are hand-painted, which makes each one slightly different from the other. The simplicity of the dots and soft lines that make up the face of a kokeshi doll gives a richness to its expression that keeps changing depending on how and from which angle one looks at it.

MEleven types of kokeshi dolls can be found in the Tohoku region, with five of them originating from five different hot spring districts in Miyagi Prefecture. These dolls are distinct in the shape and design of their torsos. Kokeshi makers are traditionally involved in the entire process of making kokeshi — from wood cutting and carving to painting and finishing.

In recent years, kokeshi have been popular as souvenirs among both Japanese and foreign tourists. Visitors can enjoy choosing from the various types of doll. Additionally, people can experience a more proactive way to enjoy the world of kokeshi by participating in various workshops that allow them to paint kokeshi with doll makers. Two such classes are offered at Akiu Craft Park in Sendai.

http://www.city.sendai.jp/kankokikaku/akiukoge/taiken.html

TOP-TIER SAKE MADE WITH LOVE, BLESSED BY NATURE

Much of Japan’s sake comes from northern Honshu, including the Tohoku region prefectures of Niigata, Fukushima, Miyagi, Iwate, Aomori, Akita and Yamagata.

The region possesses clean and clear water flowing from mountains, a necessity for the production of quality rice, the main ingredient of sake. Water is also vital in sake brewing, as it is used in most stages, from washing and soaking rice to fermenting and bottling.

It is believed that large temperature differences between morning and evening at the region’s higher latitudes are suitable for rice cultivation. Compared to the temperate climate of other rice-growing areas, this contributes to rich flavors and large harvests.

Thanks to ingredient diversity and quality, the prefectures boast about 300 sake breweries.

Fukushima Prefecture is regarded as a water-rich area with rivers flowing down from major mountain ranges, with the Abukuma highlands and the Ou and Echigo mountain ranges supplying water to paddies.

At the Annual Japan Sake Awards 2019, sake from Fukushima received 22 Gold Prizes, making Fukushima the prefecture with the most Gold Prize-winning breweries for the seventh consecutive year.

Many of Fukushima’s prize-winning breweries are between the Echigo and Ou mountain ranges.

GETTY IMAGES

To enjoy fresh sake, it’s recommended visiting breweries that offer tours and sake-tasting.

Daishichi Sake Brewery Co. offers tours in English detailing their process. After imbibing this knowledge, another way to enjoy fresh sake is to visit local izakaya (Japanese pubs).

Niigata is also renowned for premium rice and sake. It is home to about 90 sake breweries — the greatest number of Japan’s 47 prefectures.

Among the breweries that offer tours, Imayo Tsukasa Sake Brewery offers English printed and digital materials to help visitors understand the tour conducted in Japanese.

DAISHICHI SAKE BREWERY

DAISHICHI SAKE BREWERY

IMAYO TSUKASA SAKE BREWERY

IMAYO TSUKASA SAKE BREWERY

Brewery tours

The following locations are some of the many breweries that offer tours. Some may be offered exclusively in Japanese. Please contact the individual breweries for inquiries regarding tours.

Daishichi Sake Brewery Co.

URL: https://english.daishichi.com/outline/index.html

Imayo Tsukasa Sake Brewery

URL: http://imayotsukasa.co.jp/en/brewery-en/