CRAFTS Ⅱ

THE ENDURING GLAMOR OF AN ANCIENT ART FORM

Sleek black, lustrous red and glinting gold — there is something about this combination that conveys a singular Japanese aesthetic. Prepared by a skilled chef, washoku (traditional Japanese cuisine) would be delicious no matter what it is served on, but the careful arrangement of delectable morsels on fine lacquerware conveys an elegance to a meal that is difficult to achieve with other utensils.

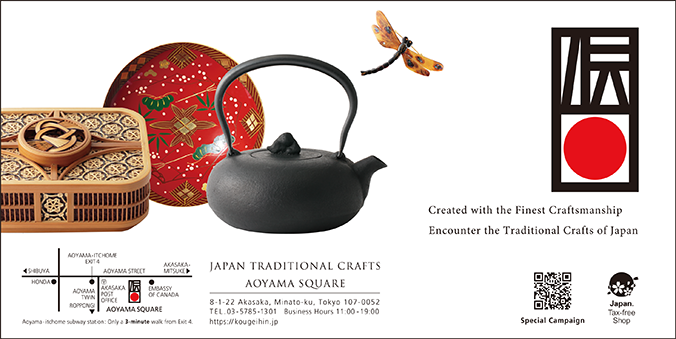

JAPAN TRADITIONAL CRAFTS AOYAMA SQUARE

A timeless art form

Japanese lacquer, or urushi, has been around for thousands of years. In fact, the oldest known lacquer item in the world is a burial accessory roughly 9,000 years old that was unearthed in Hokkaido. Lacquerware is made by applying the processed sap of the sumac tree to a base, usually made of wood. Dozens, sometimes even hundreds, of layers are applied to the base which, after hardening, create a robust protective coating that, if cared for properly, will last for generations. Fine lacquerware takes great amounts of skill and time to create, though simpler techniques and cruder materials can be used to make perfectly functional items, which is why lacquer pieces were not uncommon even in peasant households in centuries past.

In addition to eating utensils, lacquer has been applied to flower vases, religious statues, buildings, furniture and even armor and weapons. While many nations and cultures have lacquerware traditions, products from Japan are of particular renown. Urushi chests from the 16th century can be found in Spanish churches, and Marie Antoinette was known to have had a large lacquerware collection.

An imitation technique resembling lacquering even developed in Europe and was named japanning, a nod to the high esteem urushi lacquerware was held in. In this vein, the jet-black finish coating almost all pianos is said to have been inspired by lacquering.

Diverse styles

Lacquer-making is incredibly diverse even within Japan. There are 23 government-designated urushi production centers nationwide, though the craft is by no means limited to these areas.

The basic process of making a piece of lacquerware is generally the same across regions, traditions and lineages. This involves creating a wooden base, hardening it by soaking in crude lacquer, then applying a series of coats, using more refined types of lacquer for the topmost layers. The distinctive characteristics of the different production centers and craftspeople come from variations on this process — mainly in how the layers are applied, the type and quality of lacquer used and the techniques used for decoration. The latter is perhaps the easiest way to tell styles apart, and include maki-e, or the use of gold or silver powder to create intricate designs; gold inlay; mother-of-pearl inlay; and various forms of carving.

Domestic lacquer is primarily harvested in northern Japan, mostly in Iwate Prefecture, which has such a strong connection to lacquer that several places are named for it, such as Urushizawa and Urushihara in the city of Ninohe. The sap used to make lacquer is harvested by scoring a tree’s bark and collecting it in small barrels. Sap harvested at different times of the year has different properties when used to make lacquer items.

JAPAN TRADITIONAL CRAFTS AOYAMA SQUARE

Beauty with age

The sublime elegance of lacquerware, particularly of pieces decorated with precious metals, gives many people the impression that lacquer utensils are fragile and must be handled with utmost care. In fact, as long as urushi dishes are washed with a gentle detergent and dried immediately, they can be treated just like any other eating utensil. Everyday use will actually convey a particular gloss to pieces that will not emerge if they are merely put on display in a cabinet.

Lacquer dishes that break or crack can be patched using lacquer, with another layer added on top to hide the mends. A method of repairing cracked or broken pottery called kintsugi involves using lacquer as a kind of glue, then sprinkling gold powder on the wet lacquer to create glittering cracks that are left exposed. This ingenious technique of making new beauty out of a broken dish has since spread overseas.

Hands-on workshops

Aoyama Square in Tokyo’s Minato Ward is a gallery and store specializing in traditional Japanese crafts. Its collection features a diverse array of urushi items lovingly crafted in renowned production centers from Aomori in the north to Okinawa in the south. If viewing or purchasing lacquerware or other Japanese crafts is not enough, Aoyama Square holds weekly workshops at which experts from production centers throughout the country demonstrate their skills and provide opportunities for participants to try out certain techniques. In addition to urushi, workshops are held on textiles, bamboo-working, dolls, washi paper and many other art forms.