MOUNTAIN VISTAS

DIVING INTO NATURE ON JAPAN’S HIKING TRAILS

Chris Cook CONTRIBUTING WRITER

As you travel around Japan, be it from Hokkaido in the north to the southern main island of Kyushu, you can be sure of one thing: You’ll never be very far from a mountain.

This island nation, stretching some 3,000 kilometers or so from north to south, is well-blessed with peaks, and over 70% of Japan is topographically challenged in some way or another, from small hills to mountain ranges to the occasional smoking volcano.

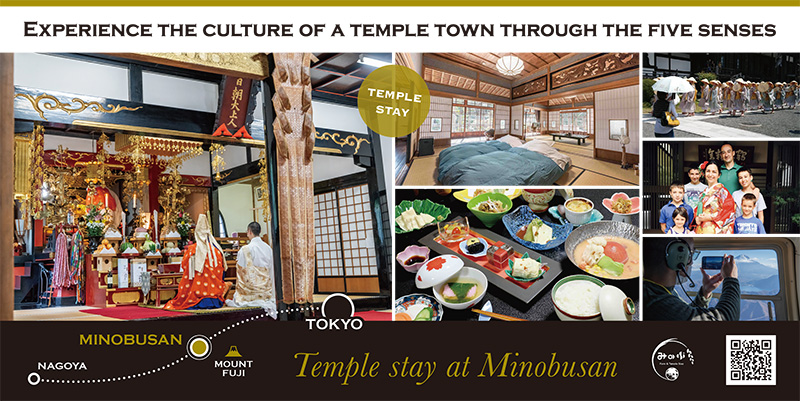

Among the most famous are 3,776-meter Mount Fuji, which rises majestically into the sky about 100 kilometers southwest of Tokyo, a slew of 3,000-meter summits to the northwest called the Northern, Central and Southern alps, which cut a jagged spine through the middle of Honshu, and restless Mount Sakurajima, the volcano across the bay from Kagoshima.

In Hokkaido is the Daisetsu range with its cluster of volcanoes and Fuji look-alike Mount Yotei, standing tall near the town of Niseko in prime skiing country on the island’s west side.

At the other end of the country are Mount Aso in Kyushu, with its ring of peaks marking the limits of a huge caldera to the northeast of Kumamoto, and Mount Miyanoura, home to moss-carpeted forests and ancient cedar trees on the island of Yakushima, some 350 km south of Aso.

In western Tokyo there’s the ever popular and easily accessible Mount Takao, where, halfway to the top, centuries-old Yakuo-in Temple can be visited. On a clear day from the summit of this 599-meter “mountain,” Mount Fuji can be clearly seen.

Another place, just an hour by train south of Tokyo, is the ancient capital of Kamakura. There, a network of pathways through creaking bamboo stands and shady forests connects many of the temples and shrines surrounding this coastal city.

In Osaka, the Mount Minoh waterfalls trail pulls in tourists and hikers alike when the autumn colors are at their peak.

The popularity of mountain hiking today is due largely to the efforts of Rev. Walter Weston, an English missionary credited with being one of the first explorers of Japan’s rocky peaks at the end of the 18th century.

Prior to this, Japan’s mountains were thought to be sacred abodes of the gods — places that were generally off-limits and where few Japanese dared to venture.

Weston’s explorations eventually helped usher in what today has become a very popular pastime, and on holidays and weekends, the trails that crisscross the country are alive with the thud of hiking boots (and often, the tinkling — or clanging — of bear bells).

There’s a network of seasonal huts on and around several of the higher mountains, and some of these facilities have been welcoming hikers for over 100 years.

But not every mountain has them. On some, such as those in the Daisetsu range in central Hokkaido, emergency huts offer shelter but unlike the more popular ones in the Alps, they are not staffed and no food is available.

Hikers who overnight in them must carry everything, from sleeping bags, gas stoves and water to pots, packages of noodles and cans of beer.

Along the more popular routes, such as those in Nagano Prefecture, the huts are open during the season (usually mid-April to late November) and accommodations and food are available during overnight stays.

For one or two people, no advance booking is necessary, but if you are with a small group you’ll need to confirm accommodations ahead of time, especially at the beginning or end of the season and around public holidays.

Camping is another option in certain places, but setting up tents away from the designated sites — usually next to mountain huts — is prohibited. Since COVID, there’s been a definite increase in the number of campers.

For instance, there’s no camping anywhere on Mount Fuji, so don’t even think about taking a tent there. However, there are campsites in several places around the base.

Besides an almost obligatory visit to Fuji-san, another popular place to experience hiking is from Kamikochi, a valley nestled below the peaks in Nagano Prefecture. Summer hiking is an institution here, and very popular with people of all ages.

By using Matsumoto as your starting point, it’s possible by using a combination of local trains, buses and taxis (private vehicles are not permitted to enter the area) to arrive at Kamikochi bus terminal in a couple of hours.

Nearby the bus terminal is a campsite set under towering larch trees. From there, the main route follows the shallow Azusa River upstream for several kilometers.

The main destinations from Kamikochi are the Hotaka range, Mount Yari (at 3,180 meters, Japan’s fifth-highest mountain) or up to Mount Choga and, further north along the ridge, to Mount Jonen and Mount Tsubakuro.

One of the benefits of hiking is that you can get close to nature. Close is perhaps not the right word: In it, touching it, feeling it are better descriptions, maybe.

During the early summer months — like right now — it’s the perfect time for botanists to look for the many species of alpine flowers.

In some places, such as the meadow at Mount Norikura, or on the grassy south-facing slopes of Mount Kita, carpets of flowers bloom as soon as the snow melts and the summer sun warms the soil.

My favorites are the delicate komakusa (Dicentra peregrina), a multispiked pink flower that grows in a small, compact mat right out of the scree, and the dainty eyebright, which nods in encouragement as you pass.

Aside from flowers, from early or mid-July onward on certain peaks above about 2,750 meters, broods of recently hatched ptarmigan chicks can often be encountered. They are easiest to find on the slopes and among the haimatsu (creeping pine) bushes around Mount Tate, which boasts the highest population of this bird in Japan.

Fuji-san is by far the best known of Japan’s mountains, and this dormant volcano (it last erupted in 1707) attracts thousands of hikers, both novice and experienced, during the brief summer climbing season.

This year the four trails will be open between early July and early September, and at all of them a variety of restrictions have been put in place.

For instance, “bullet climbing” — in which hikers begin ascending directly to the summit late in the day, watch the sunrise and descend immediately — is prohibited. There’s also a ¥2,000 climbing fee at the Yoshida trail.

This was the most popular course last year and over 137,000 climbers used it.

When hiking, your personal safety is the No. 1 consideration and, as with any outdoor pursuit, there are several things — weather, clothing, equipment, landslides, dehydration and altitude sickness — to take into consideration.

Although Japan has more peaks than anyone can physically climb in a lifetime, very few can be reached by public transport.

During the main summer tourist season, there’s a whole fleet of buses from various places waiting to whisk you up to one of the four Fuji trailheads. Boarding points include the Shinjuku bus terminal in central Tokyo, as well as Gotemba and Fujikawaguchi-ko stations.

Buses to Tatamidaira, near the summit of Mount Norikura on the border of Gifu and Nagano prefectures, start from either Hirayu Onsen or near Takayama Station.

And finally, the stunning scenery at Murodo Plateau (on Mount Tate) can be reached from Shinano-Omachi Station in Nagano Prefecture or from the city of Toyama.

For most of the time, from start to finish, you’ll be hiking on well-established trails that ascend, descend or follow the ridge lines between mountain huts. In some places, expect a certain amount of scrabbling over rocks, climbing ladders or holding onto chains affixed to the rock face. But in general, it’s fairly straightforward.

If you have time, it’s definitely worth staying overnight in a hut. But don’t expect gourmet food or the luxury of showers at altitude. A little discomfort will soon be forgotten when you witness a beautiful sunrise or sunset or take in stunning scenery like you’ve never seen before.

However, take note that for novice hikers, places like Mount Yari, the Hotaka range peaks and Mount Tsurugi are best left to more experienced hikers as there are some tricky sections — near-vertical ladders, chains and the infamous Daikiretto (great gap) heart-stopper between Mount Kita-Hotaka and Yari — to deal with.

This is not to say don’t attempt hiking in these places, but if you do, it’s a safer bet to go with someone who has been there before and who literally knows the ropes.